A small manufacturing facility in Kirkland — a clean, high-tech, extensively automated operation — has begun to churn out aerospace parts with a workforce of just two people.

Is that a bright vision of the future for a local industry that currently faces a severe labor shortage? Or a glimpse ahead to a largely peopleless dystopia?

Small aerospace suppliers in the Pacific Northwest, making parts for Boeing and other major manufacturers, have historically been low-wage operations providing mostly unskilled, entry-level jobs inside old and grimy facilities.

Autonomous Machining CEO Mike Dunlop says that, to appeal to the young, aerospace manufacturing has to change and offer “a well-paying, high-technology job rather than a dirty oily, up-to-your-elbows-in-coolant job that no one really wants to do any longer.”

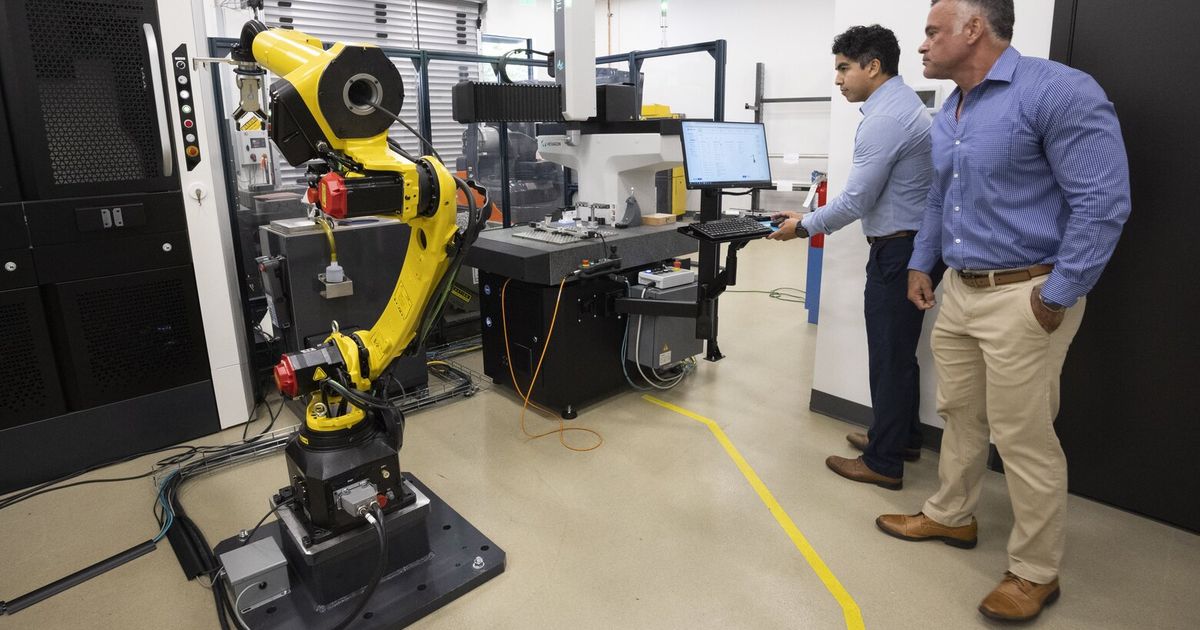

Inside a one-story building in a nondescript Kirkland business park, the veteran aerospace entrepreneur has begun to implement his alternative vision that implies a radically smaller workforce.

In an enclosed box, a computer-controlled lathe machines a metal rod, turning and shaping an airplane cockpit doorknob.

A robot takes the part out, cleans off the coolant and loads it into a separate measuring machine. Tiny rods poke out to touch the doorknob at precise points, verifying that its dimensions meet the specification.

The robot loads the finished part on a tray ready for shipping. This automated production cell can work 24/7, finishing simple parts in minutes with complete precision to whatever design engineers at the customer have specified. No one touches the machines.

This, the first of three similar cells that will be set up at the Kirkland site, has already produced components for satellites and airplanes.

Across the nation, aerospace manufacturing is facing an acute post-pandemic labor crunch. It’s hard to find people to work in the industry’s lower tiers beneath Boeing.

Federal labor statistics show that almost 14,000 workers in Washington state are currently employed in the aerospace sector outside Boeing, providing a critical network of local suppliers to the jet maker.

The Kirkland operation is a step toward how small aerospace machine shops may transform in the years ahead, with far fewer people working inside them.

“We can run 70 hours with no one here and every part perfect,” said Dunlop.

There’s no need to inspect each part, he said, because the machine that measures its dimensions is so precise.

Just two employees — machinist and manufacturing manager Joe Johnson and mechanical engineer Jerry Lugo — will run and monitor the Kirkland operation.

“They probably only need to be here four hours a day,” Dunlop said with a twinkle in his eye directed at his two employees. If anything goes wrong to hold up production, they’ll get a message on their phones.

A customer typically provides a digital model of the part needed. Using machine learning to greatly shorten the process, Lugo and Johnson create the software instructions for the machines to make the part, then test it on a virtual twin of the automated production cell.

That done, they’ll set the machines running to automatically produce real parts, each one a precise replica of the original model. Lugo’s salary this year tops $100,000 and Johnson’s $200,000.

The promise is fewer but more skilled people working clean jobs and earning high salaries.

Jon Holden, district president of the International Association of Machinists union Local 751, is wary but unfazed at the notion.

“You can’t argue against progress,” said Holden. “The modernization of facilities and plants and manufacturing is something that’s been happening for generations. We’ve dealt with that.”

“We used to have 45,000 machinists performing work in our Boeing factories, and now we’re around 30,000,” he said. “But we have capacity for way more airplanes today than we did before. And some of that is automation.”

“We’ll continue moving forward with automation and robotics,” Holden continued. “If it’s done in a way that increases capacity, it can also increase higher paying jobs.”

Transforming a plant in Renton

AIM Aerospace, with manufacturing plants in Renton and Sumner, was once a prime example of a local low-wage, low-skill aerospace supplier.

In 2015, a Seattle Times report highlighted how a 72-year-old widow with arthritis working there to support her grandson had progressed after seven years from a starting wage of $10 an hour to $13.30.

The company was bought out by a private equity firm in 2016 and then sold in 2019 to Japanese conglomerate Sekisui. Renamed Sekisui Aerospace, it’s undergoing a transformation led by Italy-born CEO Daniele Cagnatel.

He has proclaimed it his mission to bring in automation and digitization to modernize the plant — and correspondingly to raise wages.

“Forget about $18 or $20 an hour,” Cagnatel said at a local supplier conference in February. “Why can’t we pay $27, $28, $29, $30 an hour to do jobs in aerospace manufacturing?”

In an interview at the end of August at the spacious Renton facility, he said he’s hiring people at between $18 and $26 an hour, with most starting at $21 per hour or $22 per hour, then training them and raising wages as they gain skills.

He said Sekisui has hired about 250 people in the past six months. With the work demanding and plenty of low-skill alternative jobs available, about half of those hired left soon after they started.

Competing for workers with retail, hospitality and automotive businesses, Cagnatel reiterated his goal to elevate wages much higher.

“We can’t have a workforce paid at the bottom of the scale of wages,” he said. “You want to have a good culture. You want to have good quality. You want to have people frankly doing well in life.”

For him, automation is the way to achieve that. He isn’t introducing it to do existing work with fewer people, he said, but to introduce new work, generate new revenue and boost hiring.

“Then we can actually start paying people for a more mechanized type of job,” Cagnatel said.

Sekisui’s revenue and its labor force were dealt a staggering blow not only by the pandemic, which shut down much of aerospace manufacturing in 2020, but also by Boeing’s prolonged halt to deliveries of the 787 due to manufacturing quality issues with the large fuselage structures supplied by its major partners.

Three-quarters of Sekisui’s business had been making smaller parts for Boeing jets, with many of those on the 787.

Before the pandemic, the company employed about 1,400 people with annual revenue of about $170 million. The twin shocks of the COVID-19 slowdown and the 787 delivery halt cut annual revenue to $60 million and slashed the workforce to about 550 people.

At this low point, funded by the Japanese parent company, Cagnatel embarked upon a drive to install technology to diversify production into new business, including making parts for urban air taxis and drones.

Sekisui is now hiring again, with the workforce at just over 650 and a goal to get to 900. Revenue next year is projected at $130 million, a third of that in new business dependent on a line of newly installed automated machines.

Those machines will make parts from thermoplastic composites, materials that are heated and molded into shape.

Previously the focus was on thermoset composites, which are shaped and then hardened in ovens. Parts must be formed and vacuum-sealed by hand before hardening, a very labor intensive job.

Thermoplastic forming is easier to automate.

On a tour of the plant, thermoplastics program manager Chad Billmire showed off the line of new machines he is testing, qualifying and certifying to be ready for mass production in the new year.

At the start, one machine takes rolls of carbon fiber, cuts and rotates the material, then uses ultrasonic acoustic vibrations and pressure to weld together multiple layers, the plies offset at various angles to add strength.

These thicker rolls are loaded on bobbins that unwind and feed into the next machine, which uses heat, pressure and then cooling to produce a solid, flat panel consisting of as many as 60 layers of the carbon fiber.

A water jet cuts this “blank” into the desired shape, and a robot loads it into an automated press cell, where it is precision-heated in infrared ovens to soften it before it’s molded into a part.

The part is finished by trimming in a computer-controlled machine tool.

Billmire said the machines can produce a part every minute or two depending on the size and complexity.

He’s already run demonstration parts through the system as it undergoes qualification testing, including small brackets, an engine blade and an engine thrust reverser door.

Billmire said a team of about seven people is needed to operate the entire sequence of machines, with some of them also doing other work elsewhere in the plant.

Making the parts with the standard thermoset hand-labor methods would take at least twice that many workers just to do the layup preparation before the part is hardened, he said.

The automation provides the opportunity to expand production and gear up for the coming rate hikes at Boeing and other manufacturers.

“It’s not possible to scale up to those volumes with a completely manual manufacturing system,” said Billmire.

Cagnatel says automation should therefore not be seen as destroying jobs.

“The threat is never automation. The threat is work reduction,” he said. “Automation can be a multiplier, accessing new revenue streams and larger volumes of work.”

“If America and Washington state are generating value, are creating new flying machines of whatever type — whether it’s air taxis, electric vehicles or a new commercial aircraft for Boeing — that’s what the purpose is,” Cagnatel said. “That generates jobs.”

In this view, Cagnatel echoed IAM union leader Holden.

But Sekisui’s workforce, which was represented by the IAM from 2013, decertified the union in 2019 after management favored and promoted an anti-union employee leading the effort.

Holden said he doesn’t know how Sekisui operates today, though he likes hearing Cagnatel wants to pay higher wages.

“That sounds great,” he said. But he quickly added that a union provides the best assurance that will happen.

“No one’s attracted to a job if you just can’t raise a family and own a home,” said Holden. “That’s the future if people don’t have the right to organize, to form a union and negotiate for what they believe is a priority.”

Cindy Pugsley, a veteran of 39 years at the company, is the top expert in the Sekisui paint shop in Renton.

She remembers how it was at AIM and sees a big change for the better under Cagnatel.

“It’s amazing now. A great place to work,” she said, backed up by a couple of colleagues. “Employees are treated like family, like we matter.”

Attracting the young

Like Cagnatel, Autonomous CEO Dunlop describes himself as on a mission to transform the aerospace supply chain for the better.

He grew up in England with emotionally remote parents and endured the torture of a boarding school. “It was utterly miserable but it made me strong,” he said.

At 26, he arrived in Seattle 50 years ago without a college degree and grasped with full measure the opportunities of America.

“This is a wonderful country,” Dunlop said. “I felt there were no constraints.”

In the past 40 years he has built or acquired five aerospace manufacturing companies, including Net-Inspect, a hugely successful quality-management software company that has made him a wealthy man.

“I feel a need to give back,” said Dunlop, now 75. “I certainly want to give something to the next generation. I think there is almost unlimited potential for them. Particularly with technology, cloud computing, machine learning.”

The problem he sees is that the aerospace supplier industry, though it provides parts for awesome and innovative products, is not attractive to young people because the manufacturing side of it is technologically backward.

“It is very much an old white-haired man’s business,” said Dunlop. “People work in miserable conditions. And they don’t have the technology.”

“A lot of the companies in California have survived by using immigrant labor, but even that’s running out,” he added. “Their children don’t want to do what their parents did.”

Dunlop said young people coming into the industry are appalled to find they must fill out paper records instead of having everything digitized and accessible on their computers or phones.

“If the industry doesn’t make it attractive, they’re not going to find people” as the current blue-collar workforce retires, Dunlop concludes. “There has to be a paradigm shift: Better paying jobs with higher skills.”

The setup at Autonomous is tiny but set to expand, tripling the machines but still with just two people running the operation.

Dunlop expects that because of the quality, speed and precision of the production process at Autonomous — “We’re holding tolerances of plus or minus two ten-thousandths of an inch” — SpaceX and Blue Origin will be among his top customers.

Keith Batie, an independent industry auditor, in July assessed the operation’s adherence to the strict aerospace standard for manufacturing quality management. It passed with flying colors.

“In my many, many years, almost a decade of doing this, I have never had a company be certified the first time without a nonconformance,” Batie said.

Praising the “significantly unique and high level of automation” at Autonomous, he forecast it “will be a benchmark” for the whole industry.

Johnson, the veteran machinist who leads the Autonomous operation, says workers in aerospace will have “mixed feelings, for sure” about this future. Some will embrace it and others will feel threatened, he said.

“But then the majority of those coming up, the younger crowd, they’re gonna love it,” Johnson said.